Accelerated evolution

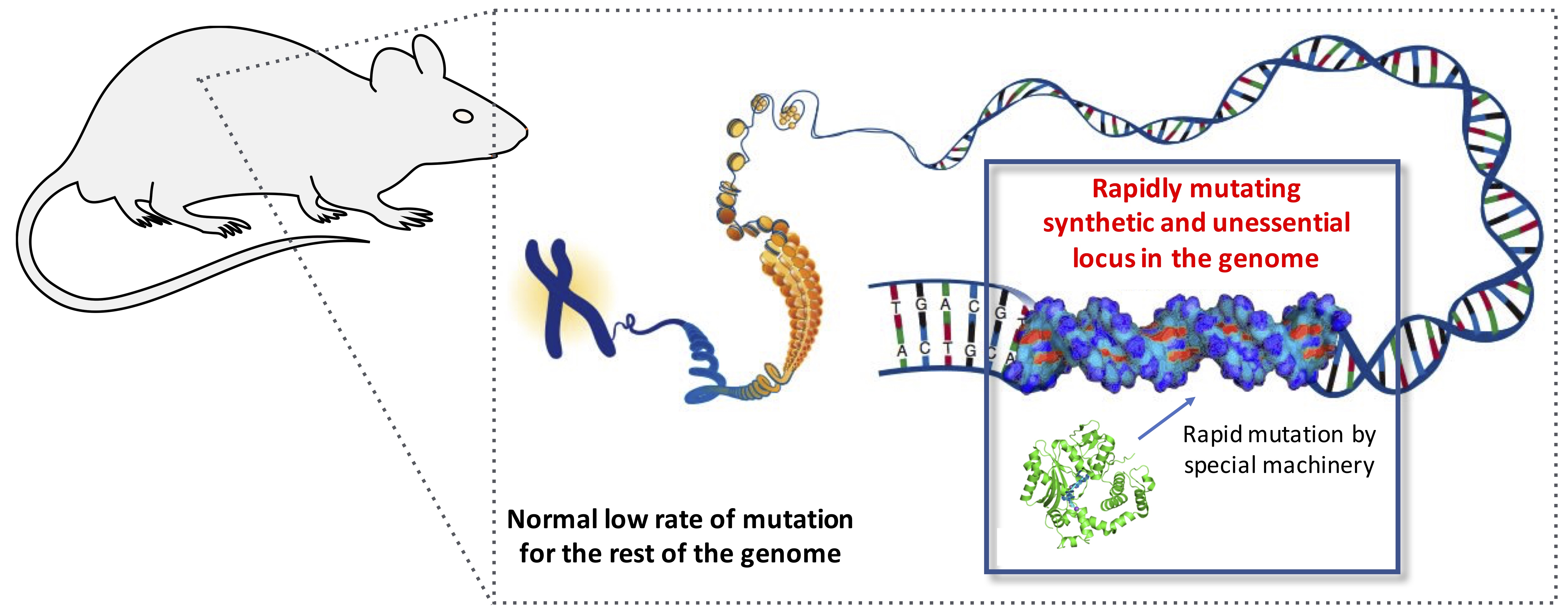

We developed orthogonal DNA replication (OrthoRep), an architecture that liberates the replication of chosen genes from the low mutational speed limits of genome propagation in order to achieve rapid continuous evolution in vivo. At its core, OrthoRep consists of an error-prone DNA polymerase that replicates a special DNA plasmid without increasing the mutation rate of the host genome. Chosen genes encoded on the special DNA plasmid autonomously hypermutate and evolve in vivo, allowing us to accelerate macromolecular evolution by thousands to millions fold at scale. With OrthoRep, we can systematically and prospectively watch, perturb, and apply evolution on laboratory timescales. We have used OrthoRep to evolve enzymes, biosensors, and antibodies, and to study the “fitness landscapes” on which macromolecular sequences travel. We focus on four key basic science questions: What does the map between macromolecular sequence and function look like? How are essentially-infinite high dimensional sequence spaces (such as those defining RNA and protein function) productively searched? How does a gene’s evolutionary past shape its future? How are new bimolecular functions born? We focus on three key application areas: sustainability through the evolution of new biocatalysts; human health through the evolution of new macromolecular therapeutics; strategic evolutionary data generation at scale to train ML models for protein design. An ambitious philosophy in the ML world is that we should aim to achieve “artificial general intelligence” and then let AGI solve all other problems. Our analogous philosophy is that we should aim to achieve “synthetic general evolution” and then let SGE solve all bimolecular engineering problems.

Recording transient non-genetic information into DNA

We have invented genetic systems that record transient information as durable mutations in DNA with the ultimate goal of making cells in developing animals keep a diary of their experiences that we can read later. Towards this goal, we have developed CHYRON (Cell HistorY Recording by Ordered iNsertion) and peCHYRON (prime editing CHYRON), systems that progressively accumulate short insertions of random nucleotides (nts) at a synthetic locus in the DNA of mammalian cells. Critically, these insertions accumulate in an ordered manner, making them clearly readable. When daughter cells inherit CHYRON loci and write additional nts to distinguish themselves, deep lineage relationships can be deduced by reading CHYRON loci. When writing is made to be inducible by cellular stimuli, CHYRON loci log the history of events a cell experiences, which can be read later by sequencing. We are using CHYRON to study normal and cancer development in animals, focusing on the key question: How does a cell’s past history influence its future?

Experimental evolution of artificial proteins and polymers

We are interested in studying how artificially designed proteins or even random sequences—maximally divorced from the natural evolutionary history of extant proteins—evolve. We are also interested in understanding the behavior and evolvability of proteins containing building blocks that nature has not used before, achieved through expanded genetic codes. We focus on four key questions: Are the statistical features defining sequence-function relationships for artificial proteins meaningfully different from those defining natural proteins? How special are natural proteins, using artificial proteins as a comparative biology? How easy do new functions emerge from sequences that have no evolutionary history? Can artificial proteins access radically new functions?

Studying atypical DNA replication systems

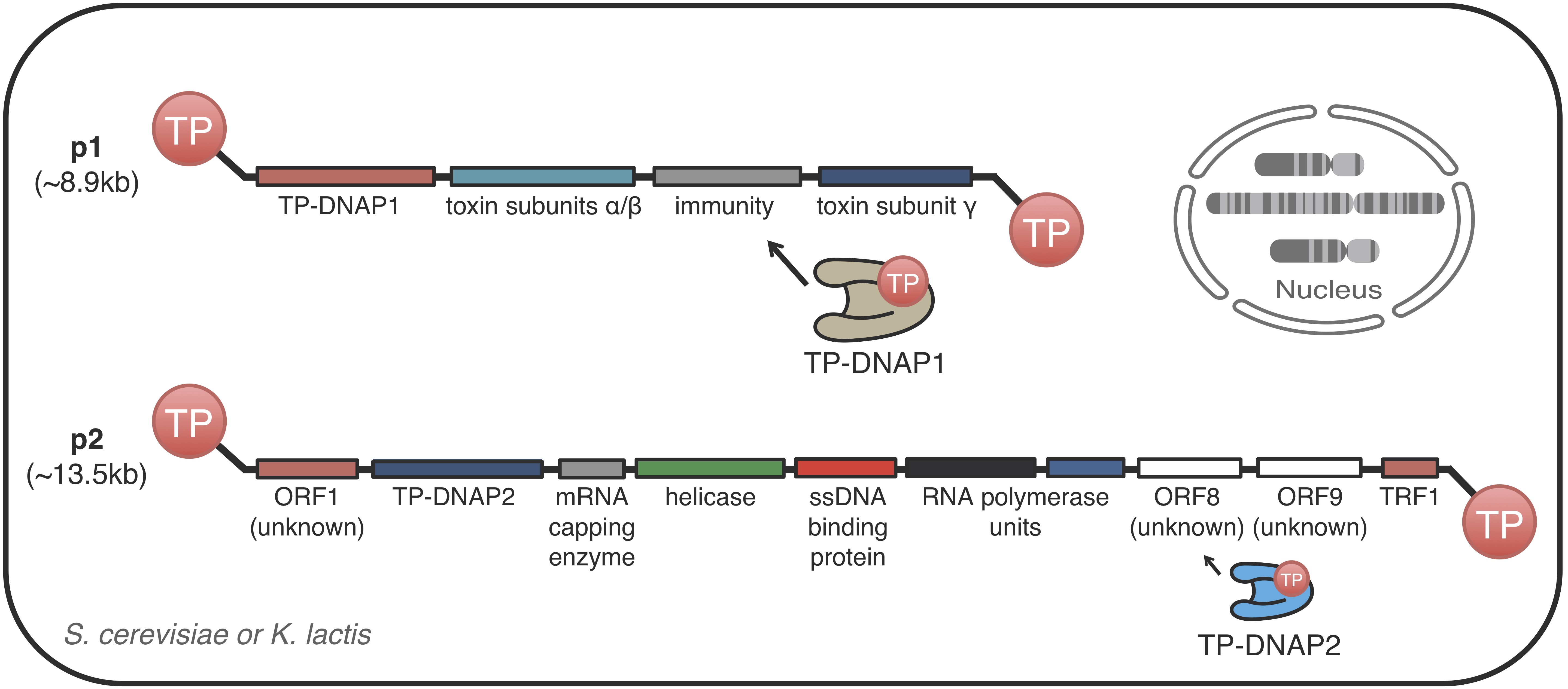

We are interested in understanding the genetics, biochemistry, and mechanistic aspects of protein-primed DNA replication systems. Such replication systems serve as the basis of orthogonal DNA replication, which is the primary reason it is interesting to us. But beyond that, protein-primed replication systems have a number of unusual biochemical and molecular properties that may 1) give us fundamental insights on the mechanisms of DNA replication, repair, and segregation, and 2) be useful substrates for applications in biotechnology and gene therapy.

Other projects

We are generally interested in engineering life to do new things that might seem impossible!